Aaronel deRoy Gruber

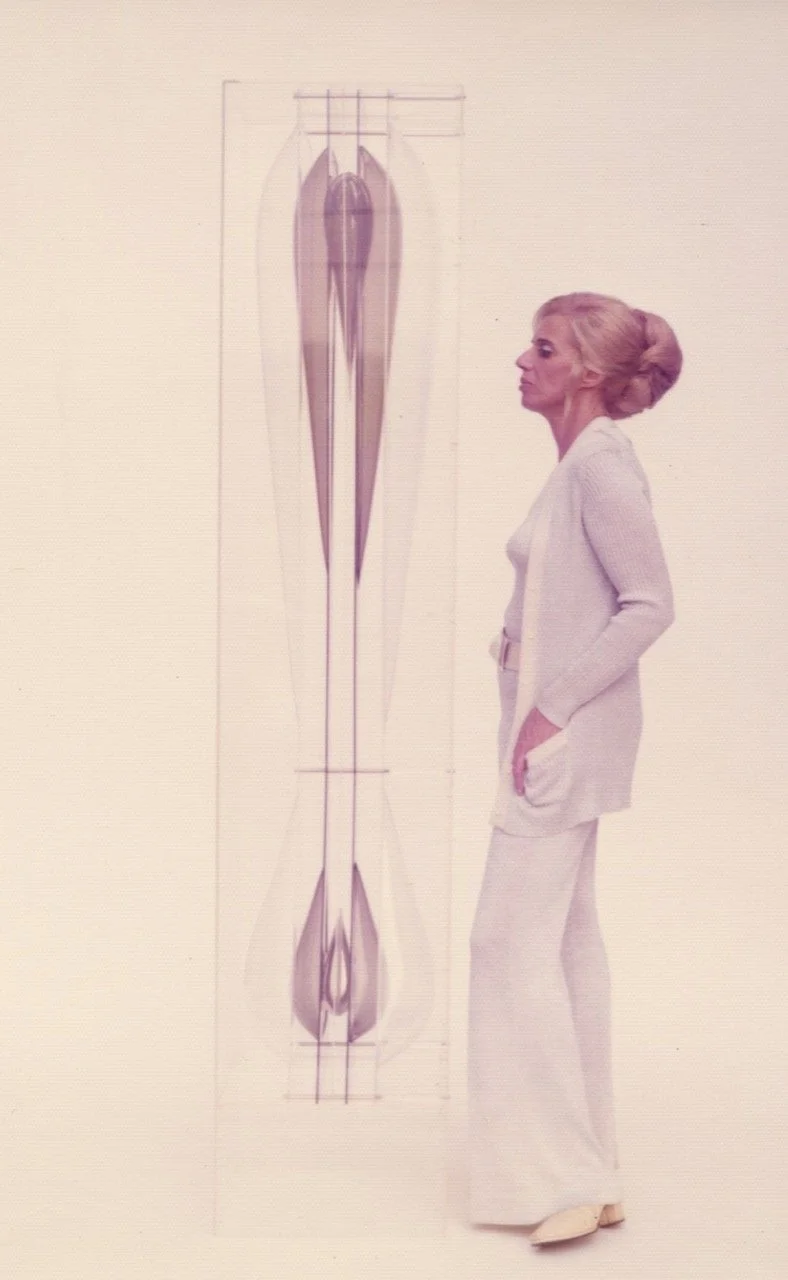

AARONEL DEROY GRUBER (1918–2011) was born Aaronel DeRoy in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She attended the Carnegie Institute of Technology Margaret Morrison Carnegie School for Women and received a BS in Costume Economics in 1940, marrying Irving Gruber the same year. Faculty artists Robert Lepper, Samuel Rosenberg and Wilfred Readio impacted her studies of design, painting and color theory. During high school she attended Rosenberg’s life-drawing classes at the Young Men and Women’s Hebrew Association and would return after WWII. deRoy Gruber also completed college courses at Traphagen School of Fashion, New York and worked as a coordinator at Pittsburgh’s Kaufmann’s Department Store. Her first two children arrived in 1944 and 1945 and the family settled on Beechwood Boulevard in Squirrel Hill where she had a painting studio in the basement and a nearby garage-apartment. deRoy Gruber was a closely involved member of the Abstract Group (later Group A) in its formative years, joining her past professors in the pursuit and discussion of abstract art. After the birth of a third child in 1953, her paintings were shown in solo exhibitions at Art Directions Gallery and Monede Gallery in New York in 1959 and 1961 before she turned to sculpture in steel. Her earliest work assembled found pieces from scrapyards and American Forge & Manufacturing, where she later worked with technicians to create machined geometric components. Continuing to explore dimensional surfaces and industrial material, she began working with Plexiglas and kinetic formats in sculpture, jewelry, and editions. Her work was included in the landmark group exhibition Made in Plastic at the Flint Institute of Arts in 1968 and in solo exhibitions with Galeria Juana Mordo, Madrid, and with her gallerist Bertha Schaefer, New York. Later in her career, Gruber turned to photography, employing both analog and digital processes to explore interplays of transparency and reflection that defined her sculpture.